For decades, marine biologists had only whispers and fragments of evidence about a whale shrouded in mystery—the ginkgo‑toothed beaked whale, Mesoplodon ginkgodens.

With males reaching over 4 meters in length and sporting tusk‑like teeth, it was one of the least understood large animals on Earth.

Despite this, no one had ever captured a live photograph of the species at sea, leaving the ghostly creature a lingering enigma in the deep, until now.

Cryptic Behavior

Beaked whales dive deeper than almost any mammal, sometimes for over an hour at a time, surfacing only briefly in remote offshore waters.

Their cryptic behavior means that entire species can go undocumented while facing growing human pressures, including industrial fishing and powerful military sonar.

Conservationists warn that it is impossible to protect animals that scientists cannot reliably find, count, or even recognize.

Whale Enigma

The ginkgo‑toothed beaked whale was first described in 1958 after a stranded carcass near Tokyo, Japan, revealed its unusual leaf‑shaped teeth.

For the next six decades, nearly all records came from dead animals washed ashore in the western Pacific, mainly Japan, or caught as bycatch.

Scientists knew almost nothing about its coloration, social behavior, or true range in the open ocean.

Mystery Signal

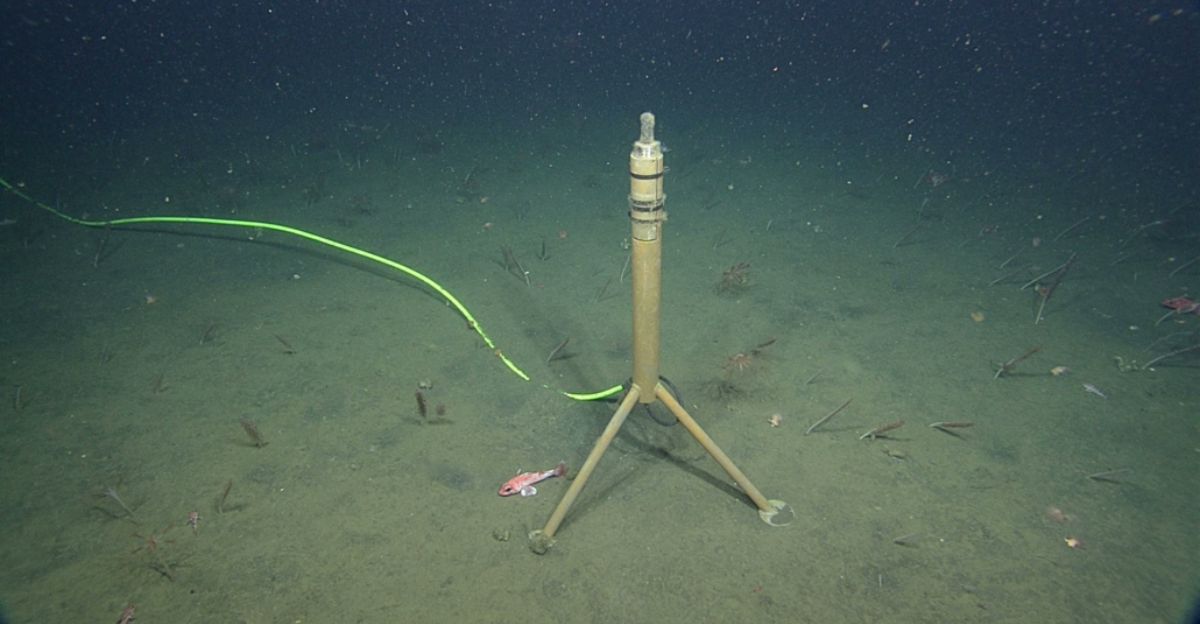

In 2018, hydrophones deployed in the North Pacific began picking up a repeated echolocation pattern dubbed “BW43,” which was clearly from a beaked whale but matched no known species.

Beginning in 2020, a binational team of U.S. and Mexican researchers towed listening arrays off Baja California each summer, suspecting either ginkgo‑toothed or Perrin’s beaked whales.

After four seasons of searching without a confirmed sighting, doubts began to grow.

First Live Proof

The breakthrough occurred in June 2024, when researchers aboard Oregon State University’s vessel, the Pacific Storm, finally spotted six beaked whales surfacing off the coast of Baja California, Mexico.

Photographer Craig Hayslip documented the historic encounter while veteran cetacean biologist Robert Pitman collected a tiny skin biopsy from an animal that approached within about 20 meters of the stern.

DNA tests confirmed five of the six whales were ginkgo‑toothed beaked whales—the first scientifically verified live sightings and photographs of this species.

Mexico’s Waters

The confirmed encounter occurred in deep offshore waters of Baja California, on Mexico’s Pacific coast, an area increasingly recognized as critical habitat for multiple beaked whale species.

Earlier, BW43 calls had been repeatedly logged northwest of the peninsula, but only the 2024 expedition linked them to a living animal.

Researchers now believe ginkgo‑toothed beaked whales use waters off Baja California and California far more regularly than previously assumed.

An Unbelievable Moment

On deck, the scientific revelation was deeply personal. Lead researcher Elizabeth Henderson, a bioacoustics researcher at the U.S. Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific, recalled the moment: “I can’t even describe the feeling because it was something that we had worked towards for so long.”

Years of searching had hinged on a few seconds of surfacing and a single successful biopsy in calm seas.

Navy’s Role

The U.S. Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific played a leading role in the multi-year effort, motivated in part by the Navy’s need to understand how its sonar affects elusive deep-diving whales.

Henderson and colleagues combined acoustic surveys, visual observers, and biopsy work over five field seasons beginning in 2020.

Their peer‑reviewed paper in Marine Mammal Science formally links BW43 to ginkgo‑toothed beaked whales and documents their first live photographs at sea.

Larger Whale Picture

According to the Society for Marine Mammalogy, there are 94 accepted cetacean species worldwide, and roughly 25% are beaked whales.

Many in this group remain poorly known, even as industrial noise, ship traffic, and climate‑driven habitat shifts intensify.

The ginkgo‑toothed discovery underscores how even large marine mammals can go virtually undocumented while global conservation debates focus on more familiar whales.

Solving BW43

The same expedition that secured the biopsy also cracked a longstanding acoustic puzzle. By matching the biopsy‑confirmed animals with simultaneous BW43 recordings, the team proved that this mysterious signal belongs to ginkgo‑toothed beaked whales.

That means scientists can now track the “ghost” species using passive acoustic monitoring alone, mapping its distribution across the North Pacific without needing frequent visual encounters.

Hard‑Won Success

Behind the breakthrough lay years of frustration. Henderson, Pitman, and colleagues, including Gustavo Cárdenas and Jay Barlow, spent every summer from 2020 searching Baja’s offshore canyons.

They endured long days of empty horizons, false acoustic leads, and fleeting silhouettes that vanished before cameras or crossbows could be readied. Henderson later called the 2024 confirmation a reward for “effort and determination” that nearly stalled.

Shifting Assumptions

Before the 2024 find, two earlier strandings on North America’s west coast were treated as anomalies—sick or wandering ginkgo‑toothed whales far from their presumed Asian core range.

The new paper argues instead that these animals likely occupy waters off California and Baja California year‑round.

That reinterpretation forces scientists to reconsider past data and redraw species distribution maps across the eastern Pacific.

From Bones to Behavior

For the first time, researchers could describe live coloration and scarring patterns in ginkgo‑toothed beaked whales.

Observers reported adults and juveniles with paler heads, dark eye patches, and distinctive pale eye spots, along with long white scars from male‑male combat and circular wounds likely from cookiecutter sharks.

Such visual details, absent from decades of stranding records, now help distinguish this species from similar beaked whales at sea.

Remaining Skepticism

Despite the landmark paper, experts stress that much remains unknown. Population size, calving rates, and precise migration patterns remain uncertain, drawing caution from conservation biologists.

Some note that live encounters are still counted in single digits, and acoustic detections, though frequent, cannot yet yield robust abundance estimates.

As a result, calls continue for expanded monitoring and increased international collaboration before major management decisions are made.

What Comes Next

Now that BW43 has an owner, researchers can deploy fixed recorders, towed hydrophones, and drifting buoys across the North Pacific to map ginkgo‑toothed habitats.

Pitman emphasizes that matching calls to all beaked whale species will allow scientists to estimate numbers and trends remotely.

That, in turn, could inform ship routing, sonar planning, and protected-area design, but only if governments act on the new data.

Growing Scrutiny

The discovery lands amid growing scrutiny of naval sonar and deep‑sea industrial noise. Previous mass strandings of other beaked whales have been linked to intense mid‑frequency sonar exercises, raising fears for cryptic species like ginkgo‑toothed whales.

Deep‑diving cetaceans face mounting threats from military sonar systems that can trigger fatal decompression events.

By clarifying where these animals live, the new research could inform environmental impact assessments and prompt defense agencies to adopt stricter mitigation measures in sensitive offshore canyons.

Mexico’s Broader Significance

The confirmed encounter off Baja California opens new questions about the species’ true range. Before this discovery, researchers had suspected that ginkgo-toothed whales occupied primarily Asian waters.

The 2024 sighting and DNA confirmation suggest the species may inhabit far greater portions of the Pacific than previously recognized, making Mexico’s waters and the broader North Pacific region a priority for future research and protection efforts.

Environmental Threats

Beaked whales’ deep‑diving lifestyle makes them vulnerable to rapid ascent when startled by loud sounds, potentially causing lethal decompression‑like injuries.

Studies suggest military sonar can disrupt foraging and drive strandings in several species.

With ginkgo‑toothed whales now confirmed in busy North Pacific waters, scientists warn that unmanaged sonar, seismic surveys, and high‑seas fisheries could silently endanger a population only just brought into view.

The “Ghost” Whale

The idea of a “ghost” whale—huge yet unseen—has captured public imagination from Japan to Mexico. Media accounts highlight how something larger than a car could remain practically invisible in the 21st century, challenging assumptions that modern technology has mapped every corner of the planet.

The ginkgo-toothed whale’s story now features in outreach efforts by aquariums and NGOs to illustrate the mystery and resilience of the ocean.

Significant Scientific Discoveries

This first‑ever live documentation of ginkgo‑toothed beaked whales shows that significant scientific discoveries still await in deep oceans.

It also illustrates a paradox: species can be both newly revealed and already at risk from human activity.

As Henderson and colleagues turn their attention to even more elusive beaked whales, the Baja finding raises a broader question—how many other “ghost” creatures remain unheard beneath the waves?

Sources:

Live Science Oct 2025

Euronews Green Nov 2025

IFLScience 2025

ORCA 2024

Marine Mammal Science 2025

U.S. Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific 2024-2025

Society for Marine Mammalogy