Something is devouring the ocean from the inside out. In the span of just three years, a mysterious pathogen has obliterated 99.7% of sea urchins off the coast of Tenerife—a decimation so complete that an entire species teeters on the edge of local extinction.

Scientists don’t know what it is. They don’t know where it came from. And they have no idea how to stop it. What they do know is terrifying: the killer is still spreading, and the clock is running out.

A Silent Underwater Pandemic

While the devastation is most visible in the Canary Islands and Madeira, this is not an isolated incident. The die-off is part of a massive, simultaneous mortality event striking Diadema species in the Caribbean, Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean.

Researchers describe it as the first pandemic to affect these populations globally simultaneously, transforming once-thriving underwater communities into graveyards from the eastern Atlantic to the Sea of Oman.

‘Zombie’ Symptoms

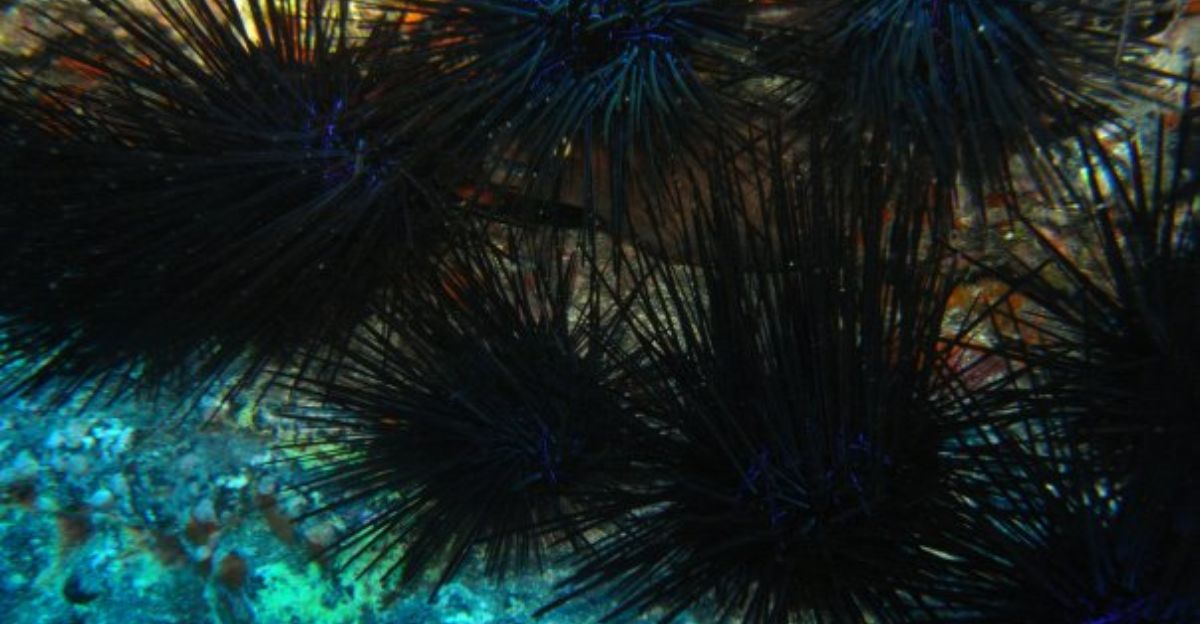

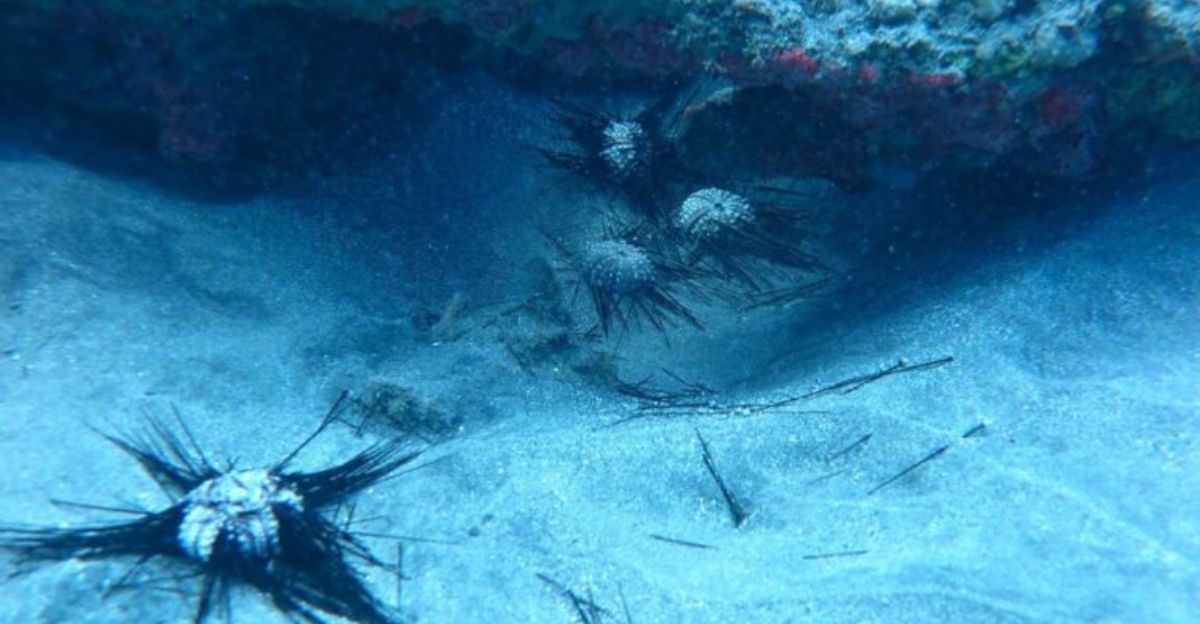

The end comes quickly and gruesomely for infected urchins. According to the study, the animals first become lethargic and stop responding to threats. Soon after, they lose their ability to cling to rocks. In the final stages, their flesh disintegrates, and spines fall off, leaving only bare skeletons behind.

This rapid deterioration has been observed consistently from La Palma to Gomera, wiping out colonies in a matter of days.

Scientists Chase A Phantom Killer

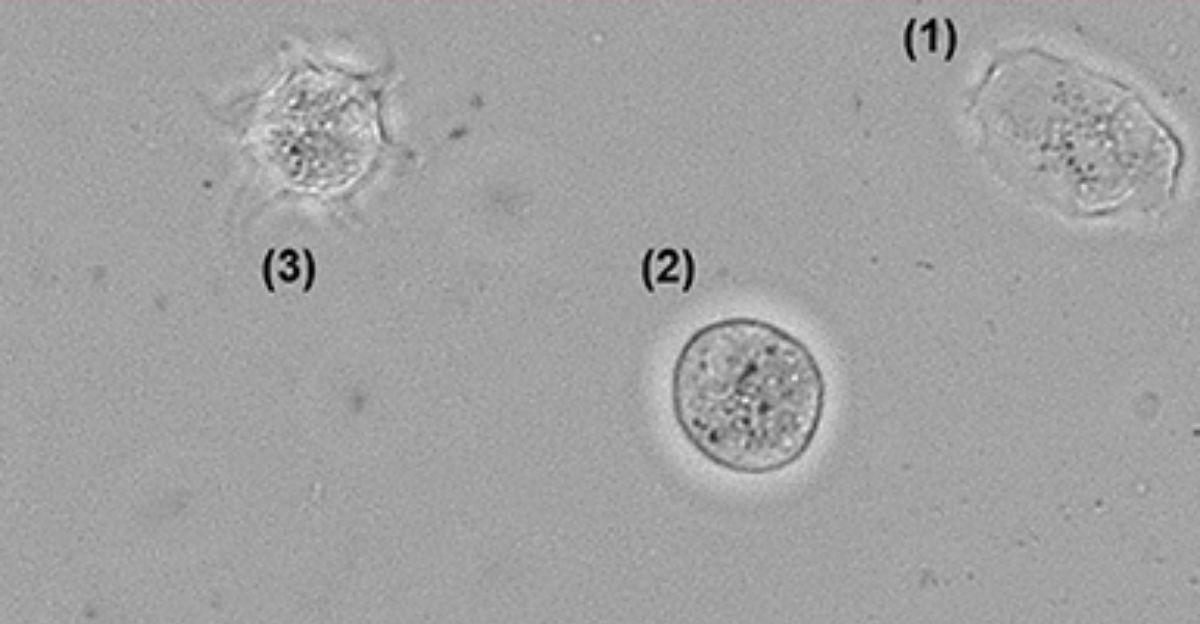

Scientists are racing to identify the killer, with suspicion falling on a scuticociliate ciliate from the genus Philaster. These single-celled parasites have been linked to similar Diadema die-offs in other regions.

The mystery deepens because previous mortality events in the Canaries were associated with a different pathogen, the amoeba Neoparamoeba branchiphila. The exact identity of this current agent remains unconfirmed, complicating efforts to stop the spread.

Spread From West To East

The contagion first emerged in February 2022 around the western islands of La Palma and Gomera. Throughout that year, it moved relentlessly eastward, eventually engulfing the entire archipelago. Unlike a standard outbreak that burns itself out, this event struck in waves.

After the initial devastation in 2022, a second wave hammered the remaining populations in 2023, ensuring that even isolated survivors were hunted down by the pathogen.

The Horror Deepens

The Canary Islands have weathered storms before. Similar mass mortality events occurred in early 2008 and 2018, killing roughly 93% of urchins off Tenerife. Populations rebounded relatively quickly. In stark contrast, the 2022 event has been followed by silence. Three years later, there is no recovery—only continued decline.

This absence of resilience signals a fundamental shift, suggesting the ocean may have lost its ability to heal itself.

The Next Generation Is Already Gone

The most alarming finding from the University of La Laguna study is a total reproductive failure. During the peak spawning season in September 2023, researchers caught almost no larvae in their traps. By January 2024, surveys of shallow rocky habitats—usually nurseries for young urchins—detected zero early juveniles.

With no new generation to replace the dead, the species faces a genetic dead end and potential local extinction.

Strange Ocean Swells

Nature often leaves clues in the weather. Researchers noted that the 2022 outbreak followed a period of strong southern swells and unusual wave activity. This pattern matches the conditions preceding the 2008 and 2018 die-offs, suggesting a dangerous link.

Experts hypothesize that these turbulent conditions might stress the urchins or transport the pathogen from deeper waters, creating the perfect storm for a biological catastrophe to take hold.

From Pest To Ghost

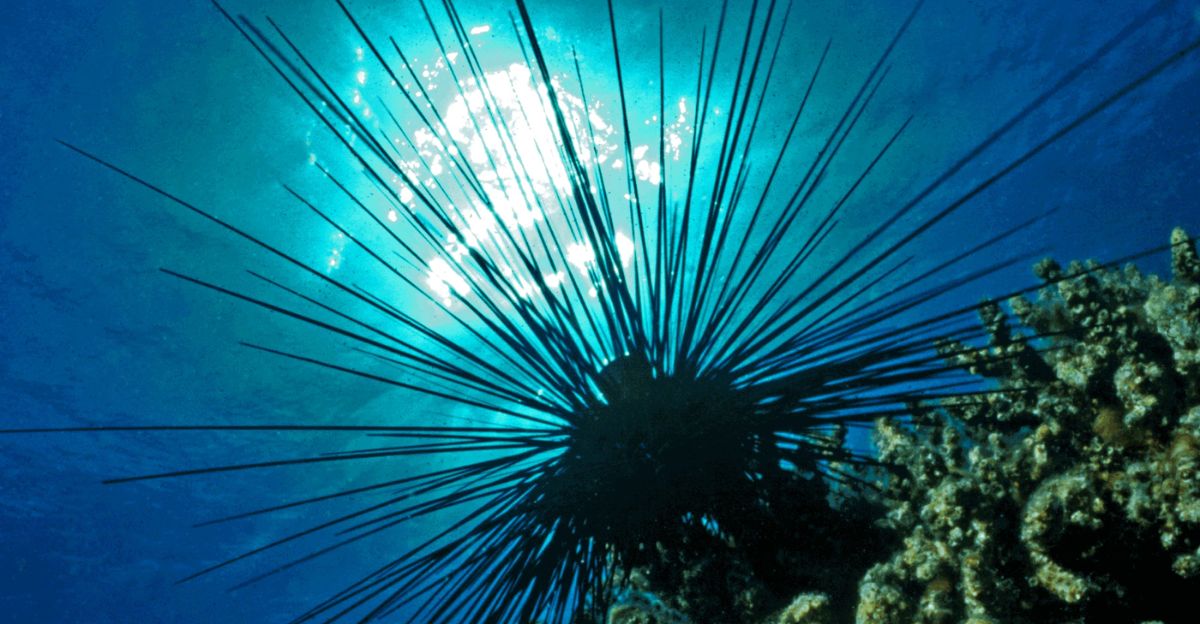

For decades, Diadema africanum was actually a problem for the opposite reason: there were too many of them. Overfishing of predators allowed populations to explode since the 1960s, creating “urchin barrens” where they stripped reefs bare.

Now, the pendulum has swung violently to the other extreme. In less than four years, 60 years of population growth has been erased, leaving reefs devoid of their most essential grazers.

Engineers Of The Reef

Sea urchins are the unsung heroes of the reef, acting as “ecosystem engineers” that keep the balance of life in check. They graze on aggressive seaweed and seagrass that would otherwise smother slow-growing corals and calcifying algae.

Without these diligent cleaners, the entire structure of the rocky reef changes. Their sudden disappearance threatens to flip the ecosystem from a diverse coral habitat into a monoculture of algae.

Starving The Ocean Food Web

The loss of Diadema africanum sends shockwaves up the food chain. These urchins are a crucial food source for a wide array of marine life, including fish, crustaceans, sea stars, and larger marine mammals. As the urchins vanish, these predators lose a staple of their diet.

The study warns that this nutritional gap could destabilize the broader marine food web, affecting commercial fisheries and biodiversity across the region.

Exhaustive Hunt For Answers

The scale of the scientific response matches the severity of the crisis. Between summer 2022 and summer 2025, the research team conducted one of the most comprehensive surveys ever attempted. They monitored 76 different sites across all seven main Canary Islands, tracking the pandemic in real-time.

This exhaustive dataset confirmed the grim reality: the decline is universal, leaving no safe havens for the species within the archipelago.

Nature Succeeded Ruthlessly

Humans tried for years to manage these populations. From 2005 to 2019, various biological control measures were implemented to reduce the overwhelming numbers of urchins in the “barrens.” Those efforts largely failed to make a dent.

Ironically, where human management struggled, this mystery pathogen succeeded with terrifying efficiency. It has accomplished in months what years of targeted culling could not, but at a cost that now threatens the species’ survival.

The Last Refuge Holds Its Breath

As the pandemic ravaged the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Indian Oceans, one major region remains curiously untouched. So far, Diadema populations in Southeast Asia and Australia have been spared from the contagion.

Scientists are closely monitoring these waters, viewing them as both a control group and a potential reservoir for the future. Understanding why these urchins are immune—or just lucky—could be the key to solving the global puzzle.

Madeira’s Mirror Image

Island borders do not contain the devastation. To the north, the archipelago of Madeira has suffered a similar fate, reporting mortality rates of approximately 90% during the 2008 and 2018 events, with current trends mirroring the Canaries’ collapse.

This shared trajectory across hundreds of miles of open ocean suggests the pathogen is highly mobile, traveling via currents or shipping lanes to hunt down Diadema colonies wherever they exist.

Extinction In Progress

The language used by the scientific community has shifted from concern to alarm. Iván Cano’s study explicitly states that abundance is at an “all-time low” and that several populations are “nearing local extinction.” This is not just a dip in numbers; it is a fundamental collapse.

The complete absence of recovery over three years indicates that Diadema africanum may effectively vanish from these waters without drastic intervention.

The Pathogen’s Rampage

While the pathogen is the direct killer, climate change may be the accomplice. The historical data shows that Diadema numbers initially climbed due to global warming and predator removal. Now, warmer oceans and altered wave patterns appear to be facilitating the disease’s spread.

This volatility—swinging from explosion to extinction—is a hallmark of an ecosystem destabilized by human-induced climate stress, making marine life more vulnerable to pandemics.

Recovery May Take Decades

The timeline for healing is daunting. Researchers estimate it could take decades for these reefs to recover, if they ever do. The unique nature of the 2022 event—specifically the second wave of mortality in 2023—suggests the pathogen is lingering in the environment.

Until the disease burns itself out or the urchins develop resistance, the reefs will remain empty, locked in a dangerous state of ecological limbo.

Will The Oceans Ever Be The Same?

As the 4-year pandemic continues, the scientific community is left with more questions than answers. The pathogen remains unidentified, the mechanism of spread is unstoppable, and the reproductive collapse is total.

The disappearance of Diadema africanum serves as a stark reminder of the ocean’s fragility. We are witnessing the erasure of a key species in real time, with the outcome still unwritten.

Sources:

“Sea urchin mass mortality in the Canary Islands and Madeira: A four-year pandemic,” Frontiers in Marine Science, 2025, DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1665504

University of La Laguna, Department of Marine Sciences, Tenerife, Spain — Research team led by Iván Cano, doctoral student

Canary Islands Regional Government Marine Surveys, Summer 2022–Summer 2025 (76 monitored sites across seven main islands)

Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean Regional Monitoring Programs — Diadema mortality tracking, 2022–2023

Caribbean Coral Reef Monitoring Initiative — Simultaneous Diadema die-off documentation, 2022–2023

International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) — Historical Diadema africanum population data, 1960s–present