In late November 2025, astronomers captured an unprecedented cosmic signature: the first X-ray emissions ever detected from an interstellar comet. As Comet 3I/ATLAS hurtled through our solar system at extraordinary velocity, advanced space observatories revealed a luminous X-ray halo stretching hundreds of thousands of kilometers from its nucleus—a phenomenon that had eluded detection in previous visitors from beyond our stellar neighborhood.

The discovery represents a watershed moment in interstellar-object research, validating decades of theoretical predictions about charge-exchange interactions between solar wind and cometary gases. More importantly, it opens new pathways for characterizing the chemical composition of objects born in alien star systems.

The Puzzle of Silent Predecessors

When Comet 2I/Borisov arrived in 2019 as only the second confirmed interstellar visitor, astronomers anticipated detecting X-ray emissions similar to those observed in solar system comets. Despite intensive observations with sophisticated instruments, Borisov remained X-ray silent. The absence puzzled researchers, raising fundamental questions about whether interstellar objects possessed different physical properties or whether observational limitations had simply prevented detection.

The enigma deepened with 1I/’Oumuamua, discovered in 2017, which exhibited unusual characteristics but departed before comprehensive spectroscopic analysis could be completed. Scientists recognized that each interstellar visitor offered a fleeting opportunity to sample material from distant planetary systems—opportunities measured in weeks rather than years.

A Narrow Window for Discovery

Comet 3I/ATLAS, discovered on July 1, 2025, by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System, presented both promise and challenge. Its trajectory would bring it relatively close to Earth in December 2025, but its position near the Sun throughout much of its approach rendered X-ray observations impossible for months. X-ray telescopes cannot safely point toward the solar disk, creating a frustrating delay as the comet brightened and then began receding.

By late November, the comet had moved far enough from the Sun’s position in Earth’s sky to permit safe observation. The window would remain open for only weeks before 3I/ATLAS faded beyond the sensitivity thresholds of current instruments. Observation campaigns had to be executed with precision timing.

Breakthrough Detection

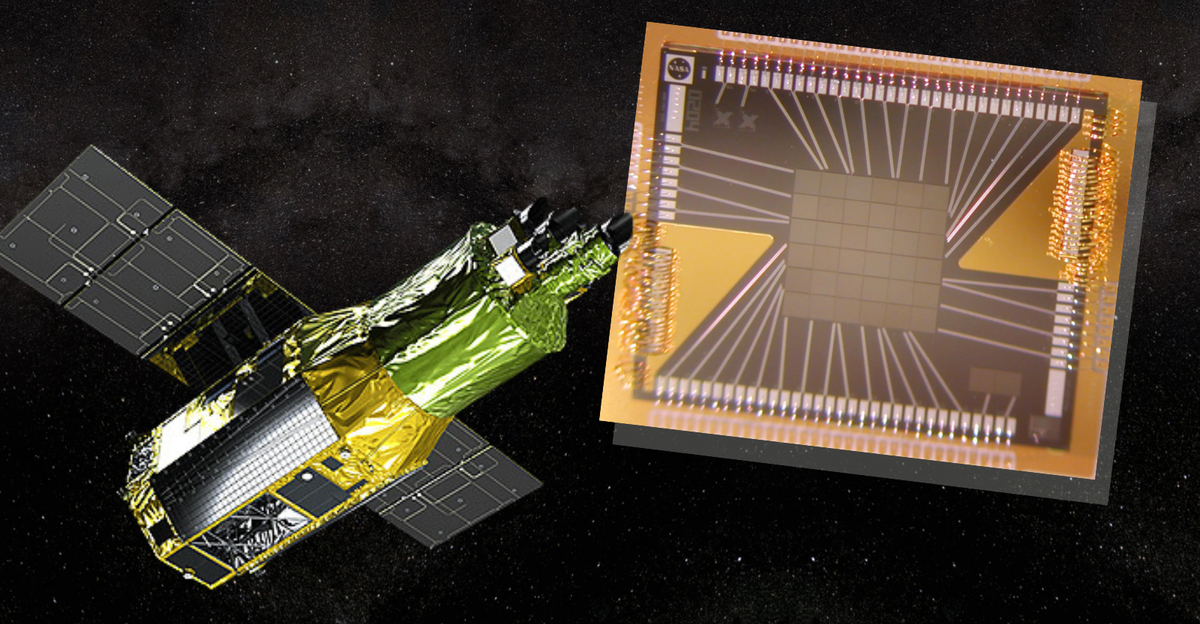

Between November 26 and 28, 2025, Japan’s X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission observatory focused its instruments on 3I/ATLAS for a cumulative 17 hours. The data revealed faint but unmistakable X-ray emissions extending approximately 400,000 kilometers from the comet’s core—a distance ten times greater than the visible coma, which measured roughly 40,000 kilometers across.

The European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton observatory independently confirmed the finding on December 3, observing the comet for approximately 20 hours and capturing striking images of red X-ray luminescence surrounding the nucleus. This dual confirmation eliminated instrumental error as a possible explanation and established the detection as genuine.

The X-ray emissions arise from charge-exchange processes, in which highly ionized particles in the solar wind interact with neutral gases sublimating from the comet’s icy nucleus. Spectroscopic analysis identified signatures consistent with carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen—elements common in cometary material but now observed in an object forged in another star system.

Implications and Future Directions

The successful detection carries profound implications for comparative planetology. If X-ray emissions from interstellar comets prove common, previous theoretical models may require revision. Researchers are now examining archival data from earlier interstellar visitors, searching for faint signals that might have been dismissed as instrumental noise.

Teams led by planetary scientists including Karen Meech at the University of Hawaii continue gathering complementary data using ground-based telescopes like Gemini North. High-resolution spectroscopy planned for early 2026 aims to map the precise chemical fingerprints of elements in the X-ray-emitting halo, potentially revealing which type of stellar environment produced 3I/ATLAS billions of years ago.

The comet passed closest to Earth on December 19, 2025, at a distance of approximately 270 million kilometers. While too faint for naked-eye observation, it remains accessible to large amateur and professional telescopes through mid-2026. Future survey instruments, including the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, will enhance humanity’s capacity to detect and study interstellar visitors, transforming rare encounters into systematic investigations. The 3I/ATLAS detection demonstrates that with coordinated international efforts and advanced instrumentation, scientists can extract meaningful data from these cosmic messengers even during brief observation windows, progressively decoding the diversity of planetary systems across the galaxy.

Sources:

JAXA XRISM Mission Team: “XRISM Observes Cometary Interloper 3I/ATLAS from the Solar Wind” (December 5, 2025)

ESA Science & Technology: “XMM-Newton X-ray View of Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS” (December 11, 2025)

NOIRLab / Gemini Observatory: “Gemini North Telescope Captures New Images of 3I/ATLAS” (December 11, 2025)

NASA / JPL Small-Body Database: “C/2025 N1 (3I/ATLAS) Orbit and Physical Parameters” (July 3, 2025)

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: “Visible and Near-Infrared Observations of Interstellar Comet 2I/Borisov” (June 2020)