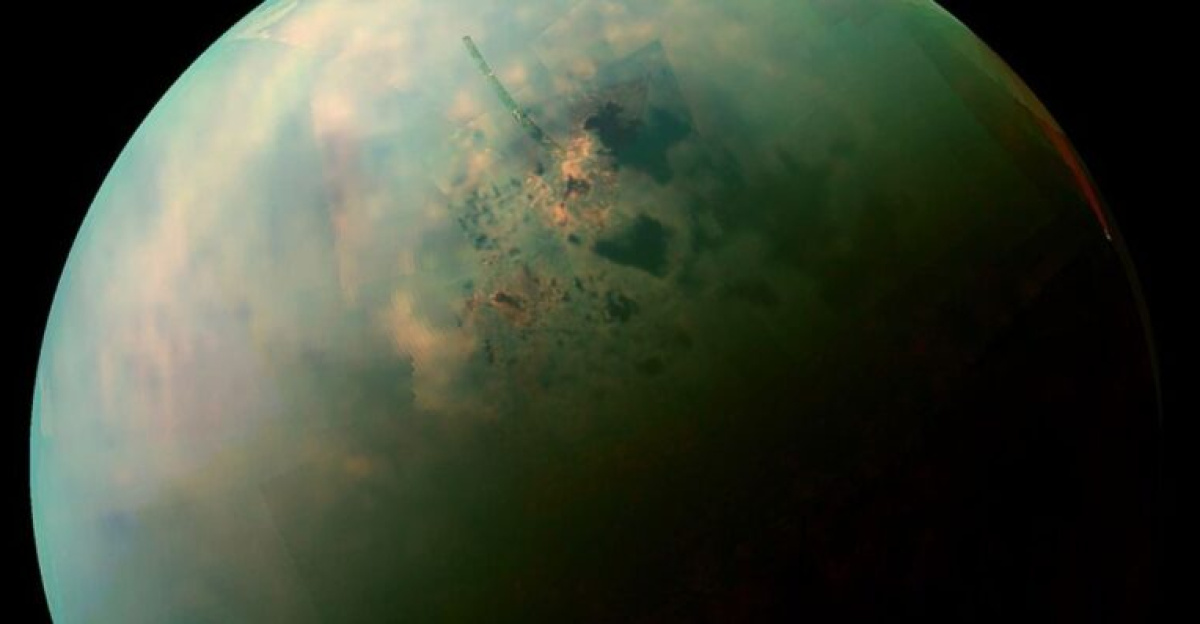

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has long puzzled scientists as a possible home for a vast underground ocean. New analysis of data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft challenges that idea. Instead of one big ocean under thick ice, Titan likely holds a deep layer of slushy, high-pressure ice with scattered pockets of warm liquid water. This discovery, published in Nature on December 17, 2025, shifts how experts view potential life spots beyond Earth.

The findings come from a closer look at Cassini’s gravity data, collected over nearly two decades. They reveal details missed before and suggest Titan’s interior acts more like thick, sticky material than free-flowing water. Lead author Flavio Petricca called it evidence of “very different environments within extraterrestrial worlds.”

Delayed Tides Reveal a Sluggish Interior

Scientists once thought Titan hid a global ocean 50 to 80 kilometers beneath its icy crust. Cassini’s gravity readings showed the moon flexing under Saturn’s gravitational pull, much like a water balloon. But a fresh review uncovered a key flaw in that picture: Titan’s surface responds to Saturn’s tug with a 15-hour delay.

This lag means the surface rises and falls out of sync, acting viscous rather than fluid. Researchers cleaned up noise in Cassini’s Doppler data and checked signals every second, not averaged over minutes. Those tweaks exposed tiny, steady “wiggles” that point to a slow, deformable interior. NASA spotlighted the result in December 2025 as proof against a full ocean.

Tidal forces from Saturn stretch and squeeze Titan constantly. In the old model, a liquid ocean would respond quickly. Here, the delay fits a structure full of stiff ice under pressure, reshaping long-held views.

Slushy Ice Layers and Warm Water Pockets

Titan’s new interior model features a 550-kilometer-deep hydrosphere dominated by exotic high-pressure ices like Ice III, Ice V, and Ice VI. A 170-kilometer shell of regular water ice sits above it, capping a dense rocky core at the center.

The standout feature? Scattered pockets of liquid water inside the slush, hitting temperatures around 20 degrees Celsius. These small, salty chambers differ from a single global sea. They could trap salts and organics at high levels, fostering rich chemistry for life’s building blocks.

No planet-wide ocean exists today. Instead, this patchy setup might suit microbes better than dilute waters. Earth examples, like briny channels in polar ice, host thriving life in tight spaces despite limited volume. Petricca’s team argues such slushy worlds could be common among icy solar system bodies.

Tidal Heat Powers the Slush

Titan generates massive internal heat from tidal friction, about 4 terawatts, four to eight times more than a global ocean model predicts. This points to a highly dissipative interior, with a tidal quality factor (Q) of 4.5. That means energy turns to heat 67 times more efficiently than in Earth’s mantle.

Friction in thick, deforming ice keeps water pockets liquid amid Titan’s deep freeze. The old ocean idea can’t match these numbers. Scientists now think Titan had a bigger subsurface sea long ago, which froze solid 1 to 2 billion years back as tides weakened.

This heating history explains the shift to slush. It also hints at how icy moons evolve, with heat sustaining life-friendly spots over eons.

Habitability in Concentrated Pockets

The new model redefines Titan’s life potential. Global oceans seemed ideal before, but small water pockets offer a twist: extreme concentration. Salts and organics could hit 100 to 1,000 milligrams per liter of carbon, far above Earth’s open seas.

Baptiste Journaux and others note these brines mimic Earth’s sea-ice channels, buzzing with microbes. Titan’s surface boosts the case. Methane-ethane lakes like Kraken Mare, bigger than the Caspian Sea, produce tholins, complex organics from UV light.

Convection or cracks might ferry these riches down to warm pockets, mixing them with heat and water. This vertical link could spark prebiotic reactions, making Titan a prime lab for patchy habitability over vast oceans.

Future Missions and Icy Moon Insights

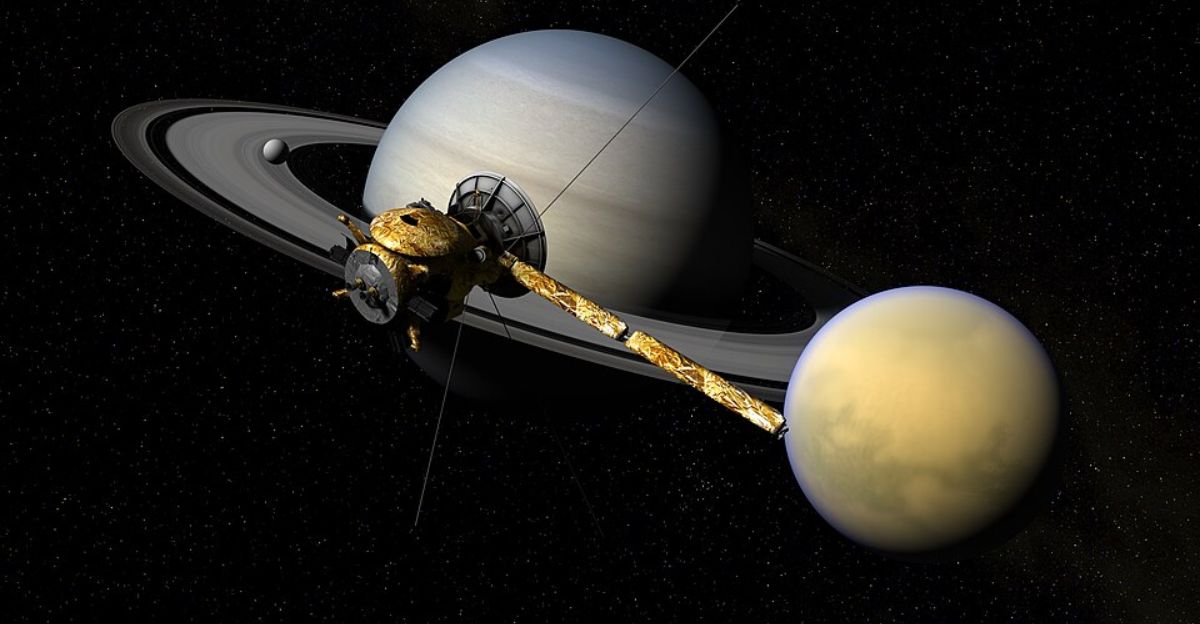

Cassini’s $3.9 billion mission (2004-2017) keeps delivering via better data tools. It now refines NASA’s Dragonfly, launching 2028 and landing 2034 for $3.35 billion. The rotorcraft will scan dunes, chemistry, and quakes with a seismometer to map water pockets.

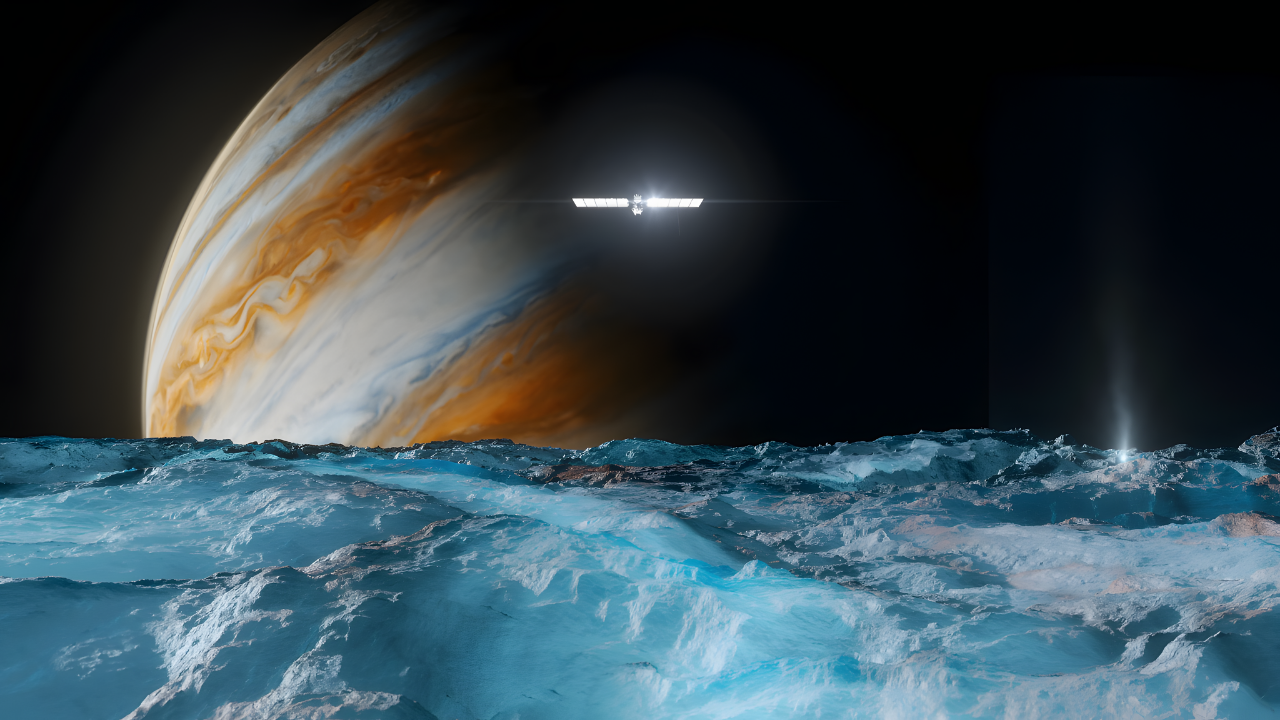

Waves traveling through ice versus liquid will reveal their depth and spread. Lessons apply broadly: Ganymede may follow Titan’s path from ocean to slush, while Europa and Enceladus keep global seas. Exoplanets around dim stars might hide similar setups.

As Dragonfly and Europa Clipper advance, experts question if concentrated niches beat uniform oceans for life. Titan shows the solar system may teem with such chemically charged hideaways, ripe for discovery.

Sources

“Titan’s strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean,” Nature, December 17, 2025.

“NASA Study Suggests Saturn’s Moon Titan May Not Have Global Ocean,” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, December 16, 2025.

“NASA Discovers Titan Doesn’t Have an Ocean, But a ‘Slushy Ice Layer,” El País (English), December 17, 2025.

“Saturn’s Moon Titan May Not Have Buried Ocean as Suspected,” PBS NewsHour, December 17, 2025.

“Titan Might Not Have an Ocean After All,” Science Magazine, December 16, 2025.

“NASA’s Dragonfly Rotorcraft Mission to Saturn’s Moon Titan Confirmed,” NASA Science Mission Directorate, April 16, 2024.