Microbes frozen in Alaska’s permafrost for 40,000 years are stirring back to life as the ground thaws, revealing a hidden threat from Earth’s warming climate. Scientists studying these ancient organisms in labs warn that their revival could unleash vast stores of greenhouse gases, intensifying global temperature rises.

The Rising Stakes

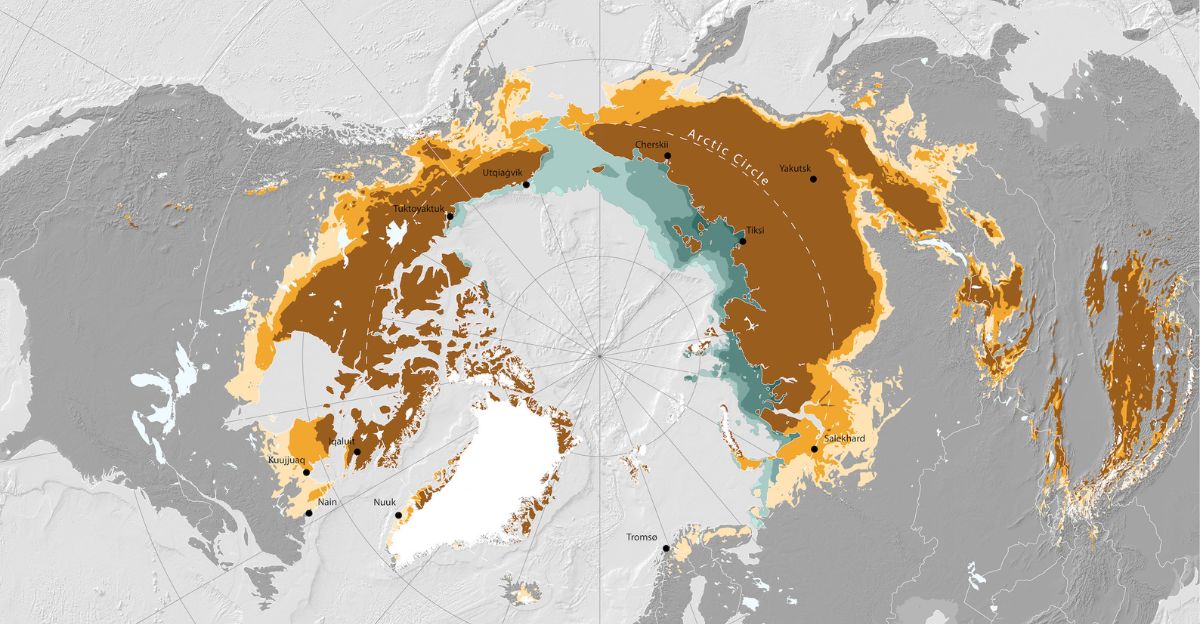

Permafrost blankets nearly a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere’s land surface, holding twice as much carbon as the current amount in Earth’s atmosphere. In Alaska, temperatures have climbed about 0.7°F per decade since the late 1970s, speeding up the thaw. This process risks releasing not only carbon but also long-dormant microbes that could decompose organic matter and emit carbon dioxide and methane.

Researchers fear this creates a feedback loop: thawing feeds microbial activity, which in turn drives more warming. The scale of permafrost—stretching across Alaska, Siberia, Canada, and Greenland—means effects could ripple worldwide.

Tunnel Into The Past

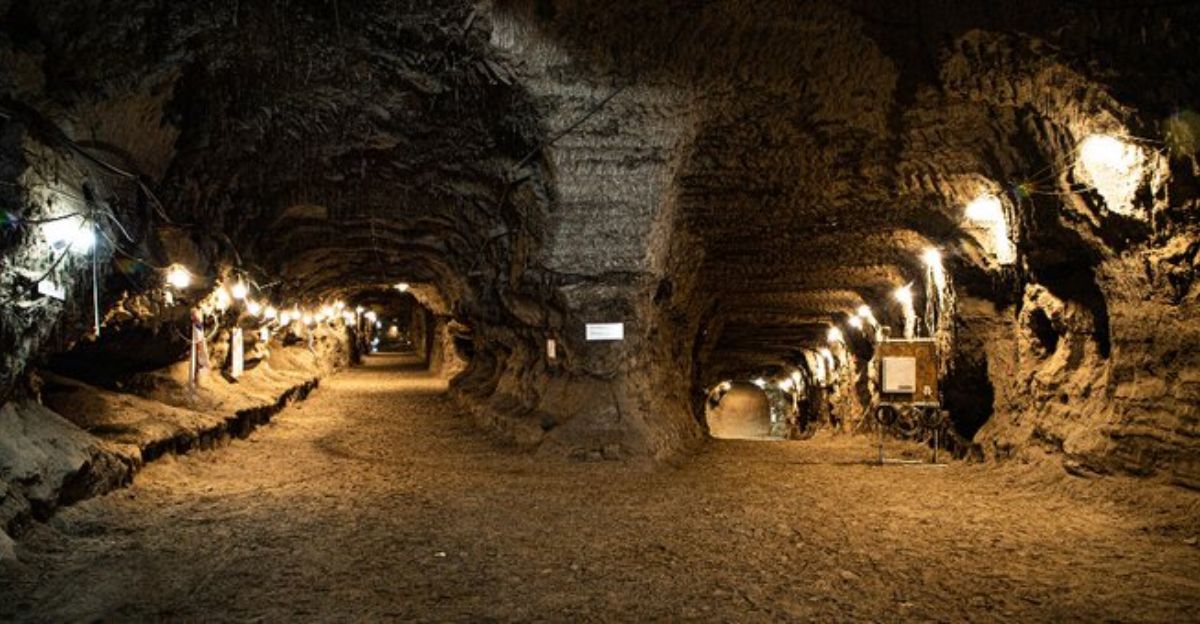

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Permafrost Tunnel, excavated in the 1960s near Fairbanks, Alaska, exposes soil up to 40,000 years old. Inside, preserved remains of plants, mammoths, and bison paint a picture of a long-lost Arctic ecosystem. The tunnel’s musty scent signals ongoing biological activity even in the cold.

A team led by Tristan Caro, now a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech, collected samples here. Collaborating with the University of Colorado Boulder and federal agencies, they transported the permafrost to labs for controlled experiments.

Ancient Life Revived

In the lab, samples aged 37,900 to 42,400 years were thawed and incubated at temperatures between 39°F and 54°F—chilly but far warmer than permafrost norms. Using deuterium-enriched water, scientists tracked microbial growth by monitoring cell membrane changes.

Activity started slowly: in the first month, only a fraction of cells turned over daily. By six months, however, the microbes had transformed. Dormant communities evolved into active ecosystems, distinct from both their ancient origins and modern counterparts. Visible biofilms—gooey, glistening colonies—formed, proving the organisms were not just surviving but thriving.

Warmer conditions did not always boost growth faster; the duration of thawing proved key. This “slow reawakening” highlights the microbes’ resilience.

Alaska’s Thawing Edge

The tunnel offers a preview of broader changes. As Arctic summers lengthen, ice-rich permafrost across Alaska could thaw widely, mobilizing microbes and carbon on a massive scale. Buildings and roads already destabilize from ground subsidence; now, microbial emissions add to the risks.

The findings challenge assumptions about frozen life’s limits. Previously revived ancient microbes exist, but this study details growth rates and community shifts, linking them directly to climate dynamics. A slight buffer exists: the months-long lag before full activity might allow refreezing to halt the process. Yet, with warming extending thaw seasons, that window narrows.

As research advances, uncertainties persist in scaling lab results to vast Arctic landscapes. The work informs policy on Arctic development, infrastructure, and emissions modeling, urging inclusion of permafrost feedbacks in global climate strategies. Revelations from Alaska’s depths underscore how the planet’s frozen past shapes its heated future.

Sources:

EurekAlert: “Researchers wake up microbes trapped in permafrost for thousands of years”

ScienceAlert: “After 40,000 Years, Microbes Are Awakening From Thawing Permafrost”

IFLScience: “It Smells Really Bad: Ancient Life Frozen in Alaska for 40,000 Years Has Been Woken Up”

Earth.com: “Ancient microbes frozen for 40,000 years revive, reorganize, and begin to devour carbon”