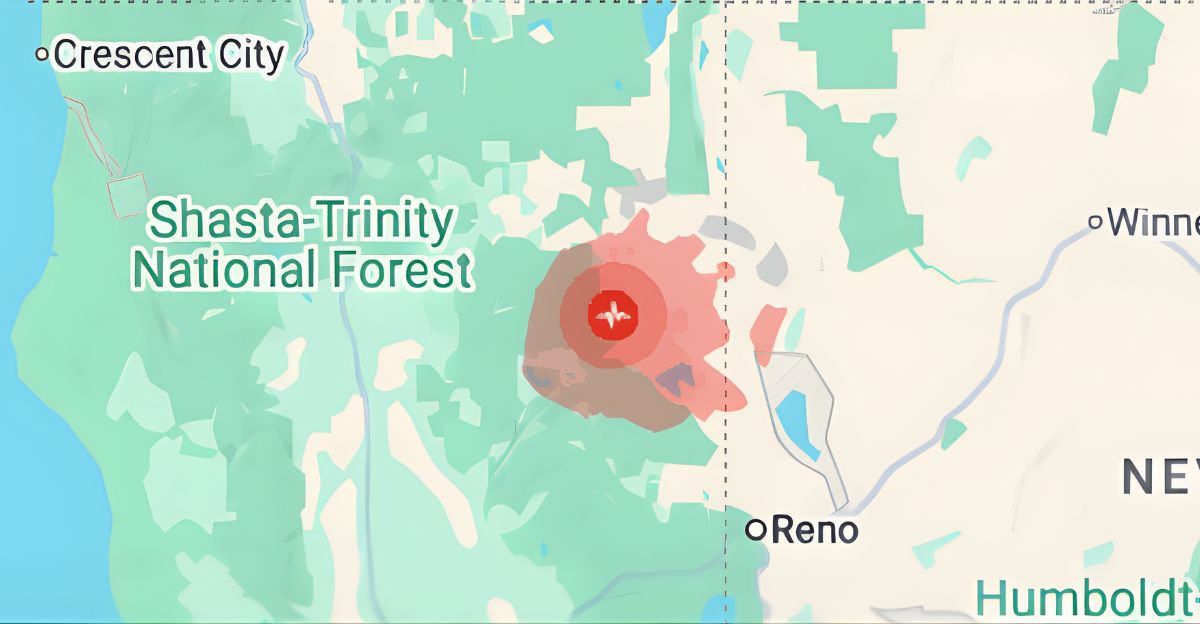

Nearly two million Californians felt the earth tremble beneath them late Sunday afternoon when a 4.7 magnitude earthquake struck near Susanville in remote Lassen County. The United States Geological Survey initially registered the quake at 5.0 before revising it downward.

What started as an ordinary December day ended with shelves rattling, items crashing to the floor, and a question nobody could answer: was this just the beginning?

A Day California Won’t Forget

The tremor hit at 4:41 p.m., shallow enough at 6.4 kilometers depth to send powerful jolts racing through the ground. Moderate shaking rocked the epicenter while lighter tremors rippled outward to Redding, Sacramento, and even Klamath Falls, Oregon. More than 300 residents reported feeling the quake, their accounts flooding into the USGS database within minutes.

But the Susanville quake wasn’t alone. Earlier that same Sunday, at 11:56 a.m., a 2.8 magnitude earthquake rattled San Ramon in the East Bay. Two quakes in one day, separated by 150 miles, left millions on edge.

When Walmart Shelves Become Seismographs

Inside the Susanville Walmart, grocery aisles turned into chaos zones as items tumbled from shelves. Residents reported hearing a deep rumble seconds before the shaking intensified. In rural Lassen County, where the population hovers around 30,000, earthquakes of this magnitude are rare enough to stop people in their tracks.

The shallow depth meant every bit of energy released by the fault translated directly into surface shaking.

Second Strongest Earthquake of the Year

A USGS representative confirmed to KRON4 that the Susanville quake tied for the second strongest in California in 2025. It shares that distinction with a 4.7 magnitude event that struck Cobb in Lake County on January 2. Only one earthquake surpassed it this year: a 5.2 magnitude tremor near Julian, east of San Diego, on April 14.

By year’s end, California logged more than 37,000 earthquakes, most imperceptible, but the handful exceeding magnitude 4.7 commanded attention.

The Fault Line Nobody Talks About

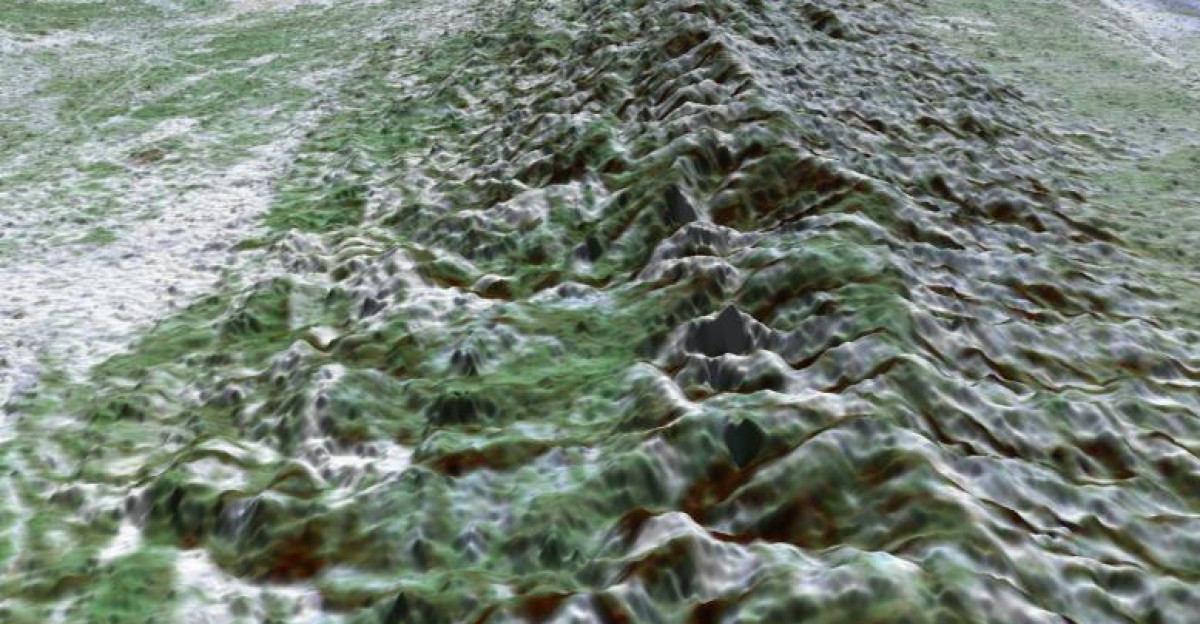

While the San Andreas Fault dominates headlines, the Susanville earthquake struck along the Walker Lane, a sprawling seismic zone running roughly parallel to the California-Nevada border. This belt of faults absorbs 15 to 25 percent of the motion between the Pacific and North American plates.

Since 2019, the Walker Lane has produced four earthquakes exceeding magnitude 6.0, including the devastating Ridgecrest sequence. Geologists describe it as a diffuse zone where the Earth’s crust is simultaneously stretching and shearing.

A Tectonic Crossroads Coming Alive

The Susanville area sits at a geological crossroads where Walker Lane strike-slip faulting transitions into the extensional faulting of the Basin and Range Province. Multiple fault systems intersect here, including the Lake Almanor fault and other northwest-trending structures.

This complexity makes the region unpredictable. Earthquakes can occur on faults that have been quiet for centuries, releasing stress accumulated over millennia.

Aftershocks Keep The Anxiety Alive

The main shock was just the opening act. In the hours that followed, a series of aftershocks rippled through the region. On Monday morning, a 2.5 magnitude tremor struck at 1:16 a.m., followed by a 2.3 magnitude quake at 6:08 a.m.

Seismologists expect the largest aftershock to measure about one magnitude smaller than the main event, meaning a 3.5 to 3.7 magnitude tremor could still be coming.

The San Ramon Swarm That Won’t Stop

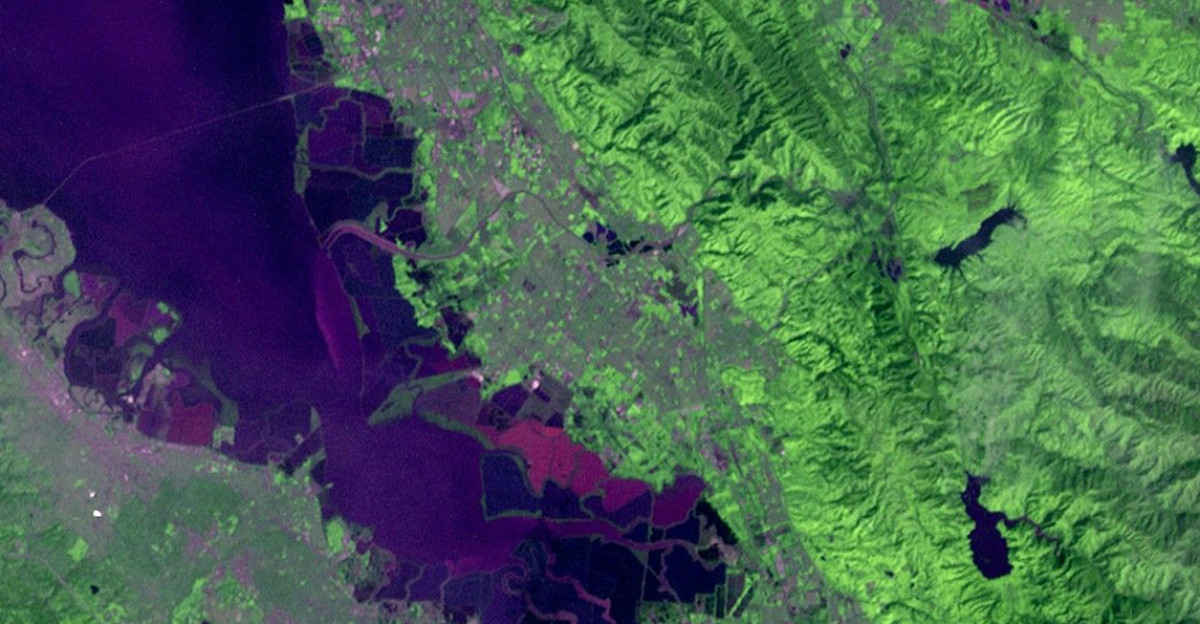

The earthquake that struck San Ramon earlier Sunday was part of a much larger story. Since November 9, at least 80 earthquakes of magnitude 2.0 or greater have shaken the area, centered near the Calaveras Fault.

The largest earthquake reached a magnitude of 4.0 on Friday, December 20, followed by a 3.9 magnitude on Saturday. Residents describe it as unsettling, a constant low-level anxiety that the next tremor could be the one that causes real damage.

Two Earthquakes, One Disturbing Pattern

The simultaneous occurrence of earthquakes in Susanville and San Ramon on December 28 raises a question that scientists struggle to answer: Are they connected? While separated by more than 150 miles and likely occurring on different fault systems, research shows that seismic waves from one earthquake can temporarily increase stress on distant faults.

Whether the Susanville and San Ramon quakes were linked through dynamic triggering remains uncertain, but the timing is striking. California’s fault systems are more interconnected than most people realize.

Why 25 Years Matters

Over the past quarter-century, California has experienced major earthquakes on fault systems most people have never heard of. The 1992 Landers earthquake, a massive 7.3 magnitude event, ruptured multiple faults over 50 miles, producing surface displacements of up to 20 feet.

The 1994 Northridge earthquake, magnitude 6.7, killed at least 57 people and caused $20 billion in damage on a previously unknown blind thrust fault. More recently, the 2019 Ridgecrest sequence reminded the world that the Eastern California Shear Zone remains capable of generating powerful quakes.

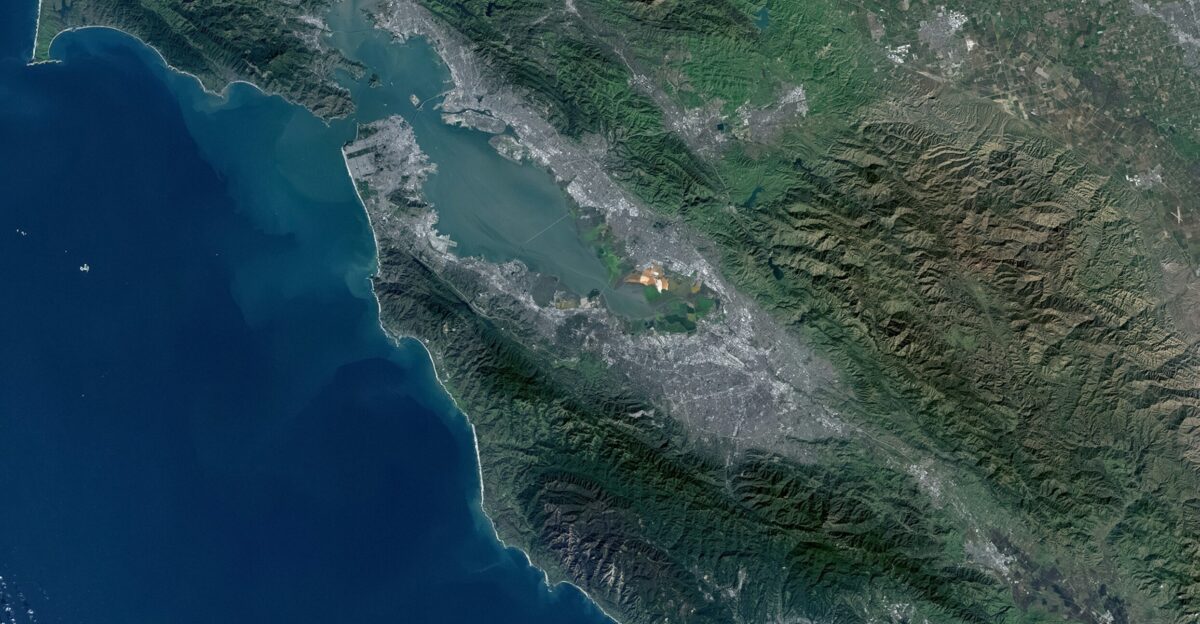

The San Andreas Myth

For decades, Californians have been told to fear the San Andreas Fault above all others. However, the Bay Area alone is home to at least five major faults capable of producing devastating earthquakes: the Hayward, Calaveras, Rodgers Creek, Concord-Green Valley, and San Andreas faults.

The USGS estimates a 72 percent chance of a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake striking the Bay Area by 2043. In Northern California, the Maacama and Bartlett Springs faults can generate magnitude 7.5 events.

Seconds That Could Save Your Life

California’s earthquake early warning system, powered by ShakeAlert and distributed through the MyShake app, provides precious seconds of warning before strong shaking arrives. The system detects the fast-moving P waves from an earthquake, calculates the event’s magnitude and location, and issues alerts before the slower, more destructive S waves arrive.

Those seconds allow people to drop, cover, and hold on, reducing injuries from falling objects. The closer you are to the epicenter, the less warning time you receive.

Drop, Cover, Hold On

Emergency management experts agree: when the ground starts shaking, drop to your hands and knees, take cover under a sturdy table or against an interior wall, and hold on until the shaking stops. This position prevents you from being knocked down and shields you from falling or flying objects.

Studies of earthquake injuries in the U.S. show that most casualties result from falling debris, not building collapses.

The Volcanic Wildcard Beneath Lassen

Lassen Volcanic Center, home to Lassen Peak, last erupted between 1914 and 1917. The presence of an active volcano adds another layer of complexity to the region’s seismic story. When earthquakes strike near volcanoes, people worry: Is an eruption coming? Scientists say no.

The vast majority of earthquakes near Lassen are caused by hot water moving through cracks in the Earth’s crust, not rising magma.

The Aftershock Danger Most People Ignore

One of the deadliest aspects of earthquakes is what comes after the main shock. Buildings already weakened can collapse during strong aftershocks, endangering first responders and residents who return too soon. There is a one-in-twenty chance that any earthquake will be followed by an even larger event, though this is rare.

More commonly, aftershocks follow a predictable decay pattern, with frequency decreasing over time. In mountainous regions like Lassen County, aftershocks can trigger landslides, especially if the ground has been destabilized by rain or snowmelt.

What Scientists Are Watching Now

The Susanville earthquake offers valuable data for seismologists studying the Walker Lane and Basin and Range. The shallow depth, moderate magnitude, and well-recorded aftershock sequence make this event particularly useful for refining models of fault behavior.

Each earthquake provides a snapshot of how stress is distributed across fault networks and how that stress is released. The ground is speaking. Scientists are listening.

A State That Lives On Borrowed Time

California has not experienced a truly catastrophic earthquake since 1994. Thirty-one years without a major urban earthquake is, by historical standards, an anomaly. The longer the wait, the more stress accumulates on the state’s major faults.

Seismologists cannot predict when or where the next big one will strike, but they can assess probabilities over longer time scales. For California, that means accepting a reality: a major earthquake is not a question of if, but when.

The Lesson From A Rural Quake

For residents of Susanville and surrounding areas, Sunday’s earthquake was a stark reminder that seismic risk extends far beyond urban centers. Rural communities face unique challenges: fewer resources, longer distances to emergency services, and older infrastructure.

The Susanville quake caused no major damage, but it could have been worse. The next tremor may not be as forgiving.

What Happens Next

As 2025 draws to a close, the Susanville earthquake serves as a sobering reminder that California’s seismic activity shows no signs of slowing. The concentration of recent activity in Northern California—from the San Ramon swarm to the Susanville quake—highlights the complexity of the state’s tectonic setting.

Scientists continue to study the Walker Lane, Basin and Range, and other fault systems to better understand how stress is transferred between faults. While predicting the exact timing of future earthquakes remains impossible, the science of seismic hazard assessment has advanced significantly. The ground will shake again. The question is: will we be ready?